Pauline and Joseph Hannen were the prime movers of racial integration in Washington in the early years of the Faith there. Initially, Pauline feared black people, but her study of Bahá’u’lláh's writings forced her to change her attitude. Pauline taught the Faith to her black washerwoman, then she and Joseph began inviting blocks to meetings in their home a rather daring thing to do at that time.

Race Unity

Though most of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá's time was spent with the rich, famous and white people, He gave special attention to their black servants, treating them no differently than their employers. On 4 August ‘Abdu’l-Bahá addressed a group of 28 black people, and spoke of the importance of unity and amity between black and white people. He told them of the upcoming marriage of Louisa Mathew, a white woman, and Louis Gregory, a black man. The white people in the audience were amazed at the influence the Cause of Bahá’u’lláh had on everyone, while the black people were very pleased to hear about such integration. Some Americans considered the creation of unity between blacks and whites to be nearly miraculous and as difficult to accomplish as "splitting the moon in half", but here was ‘Abdu’l-Bahá showing that it could happen.

While ‘Abdu’l-Bahá was living in a Paris hotel, among those who often came to see Him was a poor, black man. He was not a Bahá’í, but he loved the Master very much. One day when he came to visit, someone told him that the management did not like to have him a poor black man come, because it was not consistent with the standards of the hotel. The poor man went away. When ‘Abdu’l-Bahá learned of this, He sent for the man responsible. He told him that he must find His friend He was not happy that he should have been turned away. ‘Abdu’l-Bahá said, ‘I did not come to see expensive hotels or furnishings, but to meet My friends. I did not come to Paris to conform to the customs of Paris, but to establish the standard of Bahá’u’lláh.’

‘Abdu’l-Bahá greatly enjoyed the children. Years later He said, I had them gathered. It was very good. They were very spiritual children. There was a little girl there. Jokingly I said to her: "I want you to marry this boy." She said: "I wanted an Eastern husband."

‘Abdu’l-Bahá walked back to the hotel and said how nice it would be to eat in the gardens. The hotel manager, who recognized ‘Abdu’l-Bahá from the Denver newspapers, immediately brought out a large table and chairs. Fujita remembered that there were only five chairs at the table. When ‘Abdu’l-Bahá asked why there was no chair for Fujita, the waiter said, "Well, he is your servant." ‘Abdu’l-Bahá then said, "That doesn't matter. Make another place. It doesn't make any difference whether servant, or different color. We are all one. He should sit there, and Fujita come here". It was so beautiful. And all the Persians, five of them, around. And so, then the waiter was very much surprised, remembered Fujita later.

‘An American friend who had enjoyed the privilege of more than one visit to ‘Akka during the days of the exile of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, related an incident that took place at His table. With her sat persons of varied races, some of them traditional enemies who had now grown so to love one another that life and fortune would not have been too much to give, if called upon to do so. As the reality of their love gradually became plain to her, there was born a ray of the knowledge of the intimacy of the near ones in the world beyond. When the meal drew to a close, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá spoke of the immortal worlds. As nearly as she could remember, the words He spoke were these: “We have sat together many times before, and we shall sit together many times again in the Kingdom. We shall laugh together very much in those times, and we shall tell of the things that befell us in the Path of God. In every world of God a new Lord’s Supper is set for the faithful.”’

Agnes Parsons became a fine speaker about the Faith and always had an invitation for traveling teachers to give talks in her home. During her second pilgrimage in 1920, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá told her that she should organize the convention for the unity of the colored and white races. For a woman of her social standing to promote the unity of the black and one in the white was tradition-breaking.

Another early pilgrim was aware of the ‘bitter antagonism’ which ordinarily existed among the followers of different religious bodies. ‘For example, a Jew and a Mohammedan would refuse to sit at meat together: a Hindu to draw water from the well of either. Yet, in the house of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá we found Christians, Jews, Mohammedans, Zoroastrians, Hindus, blending together as children of the one GOD, living in perfect love and harmony.’

Arthur Parsons once commented to ‘Abdu’l-Bahá that he wished all the blacks would return to Africa, to which the Master wryly replied that such an exodus would have to begin with Wilbur, the trusted butler of the Parsons household . . . It is remarkable, then, that ‘Abdu’l- Bahá subsequently chose Agnes Parsons to spearhead the Racial Amity campaign initiated by the Bahá’í community and just as remarkable that she transcended her social milieu in order to carry out this mandate.

At that time, Washington was the most racially and socially mixed Bahá’í community in America, but it had deep racial unity problems. The upper classes, including people like Mr. and Mrs. Parsons, still upheld the long-standing social conventions of racial segregation that were not easily overcome. Many whites were afraid to host multiracial gatherings in their homes for fear of what others would say. Many blacks were also reluctant to attend meetings because of their fear of insults and discriminatory treatment. An example: once ‘Abdu’l-Bahá said He wanted to host a unity Feast. The committee organized for the event selected one of the city's most exclusive hotels one was known for its refusal to admit black people. The black Bahá’ís Thought it might be better if they did not attend and so avoid the problem of the color bar. ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, however, insisted they attend and in the end all the Bahá’ís, both black and white, sat side-by-side in the previously segregated hotel.

Howard Colby Ives tells . . . a story when about 30 of the boys arrived for their meeting: . . . Among the last to enter the room was a colored lad of about 13 years. He was quite dark and, being the only boy of his race among them, he evidently feared that he might Not be welcome. When ‘Abdu’l-Bahá saw him, His face lighted up with the heavenly smile. He raised His hand and exclaimed in a loud voice, so that none could fail to hear; that here was a black rose. The room fell into instant silence. The black face became illumined with happiness and love hardly of this world. The other boys looked at him with new eyes. I venture to say that he had been called black many things, but never before a black rose.

In late May 1912, in New York, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá was evicted from His hotel because, as Mahmud noted, of the “coming and going of diverse people” and the “additional labors and troubles” for the staff and the “incessant inquiries” directed to the hotel management. “But,” Mahmud continued, “when the people of the hotel saw His great kindness and favor at the time of His departure, they were ashamed of their conduct and begged Him to stay longer, but He would not accept.”’

In the early 30s Mother, who was divorced from her first husband, Theodore Obrig, married the Reverend Reginald G. Barrow. The wedding ceremony was performed by her father Howard Colby Ives. It is family history that they spent their wedding night on a park bench, as they could not obtain a room in a hotel in Boston. Bishop Barrow, was a man of color, who was born in the West Indies.

Joseph Hannen records: “On Tuesday, April 23rd, at noon, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá addressed the student-body of more than 1,000, the faculty and a large number of distinguished guests, at Howard University. This was a most notable occasion, and here, as everywhere when both white and colored people were present, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá seemed happiest. The address was received with breathless attention by the vast audience, and was followed by a positive ovation and a recall.”

Juliet Thompson wrote: “Gently yet unmistakably, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá had assaulted the customs of a city that had been scandalized only a decade earlier by President Roosevelt’s dinner invitation to Booker T. Washington. Moreover as a friend who helped Madame Khan with the luncheon recalled, the place setting that ‘Abdu’l-Bahá had rearranged so casually had been made according to the strict demands of Washington protocol. Thus, with one stroke ‘Abdu’l-Bahá had swept away both segregation by race and categorization by social rank.

Louis Gregory was blessed with going on pilgrimage. Towards its end ‘‘Abdu’l-Bahá summoned Louis Gregory and Louisa Mathew, a white English pilgrim. He questioned them, and, to their surprise, expressed the wish that they should join their lives together. In deference to His wishes they were married, and he sent them forth as a symbol of the spiritual unity, cooperation, dignity in relationships and service He desired for the races of mankind. That marriage presented many challenges. It brought all the obstacles to understanding and amity, and often cruel pressures. But it endured because the two souls it joined were ever guided and protected by a love beyond themselves and the pressures of the world. Theirs was a demonstration of the love which is prompted by the knowledge of God and reflected in the soul. They saw in each other the Beauty of God; and, clinging to this, they were sustained throughout the trials, the accidental conditions of life and the changes and chances of human experience.’

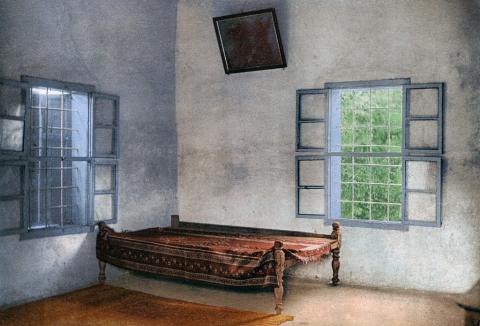

Mr Robert Turner, the butler of philanthropist Mrs Phoebe Hearst, distinguished himself by being the first Western black man to become a Bahá’í. May Maxwell recalled later that ‘on the morning of our arrival [on pilgrimage], after we had refreshed ourselves, the Master summoned us all to Him in a long room overlooking the Mediterranean. He sat in silence gazing out of the window, then looking up He asked if all were present. Seeing that one of the believers was absent, He said, “Where is Robert?” . . . In a moment Robert’s radiant face appeared in the doorway and the Master rose to greet him, bidding him be seated, and said, “Robert, your Lord loves you. God gave you a black skin, but a heart white as snow.”’ Such was the tenacity of his faith that even the subsequent estrangement of his beloved mistress from the Cause she had spontaneously embraced failed to becloud its radiance, or to lessen the intensity of the emotions which the loving-kindness showered by ‘Abdu’l-Bahá upon him had excited in his breast.’

Mrs. Parsons discreetly avoids mentioning here that ‘Abdu’l-Bahá broke with contemporary social conventions of racial separation by insisting the Louis Gregory, a prominent African-American Bahá’í, attend this luncheon in segregated Washington, D.C.even though he had not been invited. Harlan Ober tells the story. . . . “Just an hour before the luncheon ‘Abdu’l-Bahá sent word to Louis Gregory that he might come to Him for the promised conference. Louis arrived at the appointed time, and the conference went on and on; ‘Abdu’l-Bahá seemed to want to prolong it. When luncheon was announced, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá led the way and all followed Him into the dining room, except Louis.

“All were seated when suddenly ‘Abdu’l-Bahá stood up, looked around, and then said to Mírza Khan, Where is Mr. Gregory? Bring Mr Gregory! There was nothing for Mírzá Khan to do but find Mr. Gregory, who fortunately had not yet left the house, but was quietly waiting for a chance to do so. Finally Mr. Gregory came into the room with Mírzá Khan.

“‘Abdu’l-Bahá, Who was really the Host (as He was wherever He was), had by this time rearranged the place setting and made room for Mr. Gregory, giving him the seat of honor at His right. He stated He was very pleased to have Mr. Gregory there, and then, in the most natural way as if nothing unusual had happened, proceeded to give a talk on the oneness of mankind.”

On a certain occasion in America ‘Abdu’l-Bahá ‘announced that He wished to give a Unity Feast for the friends. The Committee arranging for the affair had taken it to one of the city’s most exclusive hotels, famed for its color bar. The colored friends, troubled by the prospect of insults and discriminatory treatment, decided not to attend. When ‘Abdu’l-Bahá learned of this, He insisted that all the friends should attend. The banquet was held with all the friends, white and colored, seated side by side, in great happiness and without one unpleasant incident.’

One day, Dr. Zia Bagdadi invited Mr. Louis Gregory, a black Bahá’í, to his home. When his landlord heard about this, he gave notice to Dr. Bagdadi. He was to vacate his residence because he had a black man in his home.

The following delightful story about an incident during ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s stay in New York illustrates the fact that He was not ‘colour-blind’, but rather He found racial differences a thing of beauty. When the Master was on His way to speak to several hundred men at the Bowery Mission He was accompanied by a group of Persian and American friends. Not unnaturally a group of boys was intrigued by the sight of this group of Orientals with their flowing robes and turbans and started to follow them. They soon became noisy and obstreperous. A lady in the Master’s party was highly embarrassed at the rude behaviour of the boys. Dropping behind she stopped to talk with them and told them a little about who ‘Abdu’l-Bahá was. Not entirely expecting them to take her up on the invitation, she nevertheless gave them her home address and said that if they liked to come the following Sunday she would arrange for them to see Him. Thus, on Sunday, some twenty or thirty of them appeared on the doorstep, rather scruffy and noisy, but with signs that they had tidied up for the occasion nonetheless. Upstairs in ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s room the Master was seen at the door greeting each boy with a handclasp or an arm around the shoulder, with warm smiles and boyish laughter. His happiest welcome seemed to be directed to the thirteen-year-old boy near the end of the line. He was quite dark-skinned and didn’t seem too sure he would be welcome. The Master’s face lighted up and in a loud voice that all could hear exclaimed with delight that ‘here was a black rose’. The boy’s face shone with happiness and love. Silence fell across the room as the boys looked at their companion with a new awareness. The Master did not stop at that, however. On their arrival He had asked that a big five-pound box of delicious chocolates be fetched. With this He walked around the room, ladling out chocolates by the handful to each boy. Finally, with only a few left in the box, He picked out one of the darkest chocolates, walked across the room and held it to the cheek of the black boy. The Master was radiant as He lovingly put His arm around the boy’s shoulders and looked with a humorously piercing glance around the group without making any further comment.

The Master’s every act was meaningful. On one auspicious occasion in Washington, D.C. He demonstrated what justice and love can do. The chargé d’affaires of the Persian Legation in the city and his wife had arranged a luncheon in His honour. Their guest list included members of the social and political life in the capital, as well as a number of Bahá’ís. Louis Gregory, a cultivated gentleman and employee in the government he later became the first black Hand of the Cause had been invited to visit the Master. He was surprised at the time scheduled for a visit, as he knew of the luncheon plans, but naturally he arrived on time. Their conference seemed to go on and on as if indeed the Master might be prolonging it deliberately. Eventually the butler announced that luncheon was being served. ‘Abdu’l-Bahá led the way, the invited guests following closely behind. Mr Gregory was perplexed: should he leave or wait for ‘Abdu’l-Bahá to return? The guests were seated when suddenly the honoured Guest rose, looked around and then asked in English, ‘Where is My friend, Mr Gregory?’, adding ‘My friend, Mr Gregory, must lunch with Me!’ It just so happened that Louis Gregory had not been on the luncheon list, so naturally he had remained behind. Now the chargé d’affaires hastened after him. The Master rearranged the place setting at His right, the seat of honour, of course ignoring utterly the delicate laws of protocol and the luncheon started only after Mr Gregory had been seated. Then, in a most natural manner, as if nothing at all unusual had happened in the capital that day in 1912, with tact and humour, the Master ‘electrified the already startled guests’ by talking about the unity of mankind.

The National Association for the Advancement of Coloured People (NAACP), a nationwide, biracial organization that would fight to achieve African American civil rights had invited ‘Abdu’l-Bahá to address their Fourth Annual Conference in Chicago. He spoke at the conference twice on Tuesday, April 30, 1912, once early in the afternoon at Hull House in South Chicago and then to the evening session at Handel Hall, at 40 East Randolph Street in the Loop neighbourhood.

‘Abdu’l-Bahá began His address at Handel Hall by quoting the Old Testament: ?Let us make man in our image, after our likeness.? ?Let us find out,? He proposed, ?just where and how he is the image and likeness of the Lord, and what is the standard or criterion whereby he can be measured.

Then He asked a series of rhetorical questions: ?If a man should possess wealth, can we call him an image and likeness of God? Or is human honour the criterion whereby he can be called the image of God? Or can we apply a colour test as a criterion, and say such and such an one is coloured a certain hue and he is therefore, in the image of God? Can we say, for example, that a man who is green in hue is an image of God??

?Hence we come to the conclusion that colours are of no importance. Colours are accidental in nature. . . . Let him be blue in colour, or white, or green, or brown, that matters not! Man is not to be pronounced man simply because of bodily attributes. Man is to be judged according to his intelligence and spirit. . . . That is the image of God.

‘Abdu’l-Bahá concluded by once again conflating and neutralizing common uses of the imagery of black and white, as He had done in Washington: ?If man’s temperament be white, if his heart be white, let his outer skin be black; if his heart be black and his temperament be black, let him be blond, it is of no importance.? Colour, in other words, had no effect on the content of a person‘s character.

Almost immediately across the road from Handel Hall, at the Masonic Temple at 29 East Randolph Street, another convention was underway that evening. Fifty-eight delegates from forty-three cities were about to elect nine members to the governing board of the Bahá’í Temple Unity, a national body formed to coordinate the largest project ever undertaken by the Bahá’ís in North America: the construction of an enormous house of worship north of Chicago. White fluted columns with capitals wrapped in acanthus leaves surrounded the delegates in Corinthian Hall as they cast their secret ballots.

After the first round of voting there was a tie for ninth place between Frederick Nutt, a white doctor from Chicago, and Louis Gregory, the black lawyer from Washington, DC. In a dramatic departure from the vicious 1912 Presidential election, which raged all around them, each man resigned in favour of the other.

Then Mr Roy Wilhelm, a delegate from Ithaca, NY, stood and put forward a proposal. His motion, seconded by Dr. Homer S. Harper of Minneapolis, recommended that the convention accept Dr. Nutt‘s resignation.

The delegates responded unanimously.

To have elected an African American to the governing board of a national organization of largely middle- and upper-class white Americans and to have done so at the nadir of the Jim Crow era in 1912 was rare in the extreme. Even the NAACP had only elected one black member to its executive committee when it had been formed in 1909.

‘Abdu’l-Bahá‘s assault on the colour line was beginning to bear fruit.

Faced with the segregated social pattern and laws of Apartheid in South Africa, the integrated population of Bahá’ís had to decide how to be composed in their administrative structures whether the National Spiritual Assembly would be all black or all white. The Bahá’í community decided that instead of dividing the South African Bahá’í community into two population groups, one black and one white, they instead limited membership in the Bahá’í Administration to black adherents, and placed the entire Bahá’í community under the leadership of its black population.