‘Three days after the arrival of Bahá’u’lláh and His companions in ‘Akka, the edict of the Sultan condemning Him to life imprisonment was read out in the Mosque. The prisoners were introduced as criminals who had corrupted the morals of the people. It was stated that they were to be confined in prison and were not allowed to associate with anyone. ‘Abdu’l-Bahá was summoned by the Governor of ‘Akka to hear the contents of the edict. When it was read out to Him that they were to remain in prison for ever, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá responded by saying that the contents of the edict were meaningless and without foundation. Upon hearing this remark, the Governor became angry and retorted that the edict was from the Sultan, and he wanted to know how it could be described as meaningless. ‘Abdu’l-Bahá reiterated His comment and explained that it made no sense to describe their imprisonment as lasting for ever, for man lives in this world only for a short period, and sooner or later the captives would leave this prison either dead or alive. The Governor and his officers were impressed by the vision of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá and felt easier in His presence. Some time later, when the Master emerged as the most eminent and the most loved person in ‘Akka and the neighbouring lands, when practically all of the people of ‘Akka, both high and low, turned to Him for help, and when the Governors and high officials sought His advice and sat at His feet to receive enlightenment, the edict of the Sultan together with other documents relating to the imprisonment of Bahá’u’lláh and His companions were removed from the government files and presented to ‘Abdu’l-Bahá by a government official.’

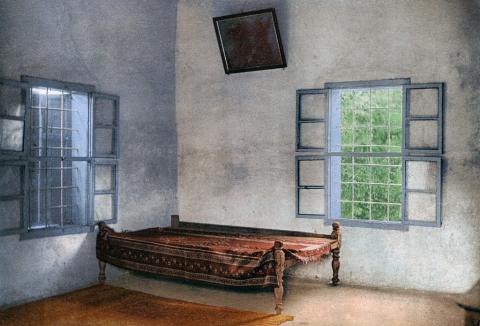

Prison - Akka

The First Summer

We had no communication whatever with the out-side world. Each loaf of bread was cut open by the guard to see that it contained no message. All who believed in the Bahá’í manifestation, children, men and women, were imprisoned with us. There were one-hundred and fifty of us 116 together in two rooms and no one was allowed to leave the place with the exceptions of four persons, who went to the bazaar to market each morning, under guard. The first summer was dreadful. 'Akká is a fever-ridden town. It was said that a bird attempting to fly over it would drop dead. The food was poor and insufficient, the water was drawn from a fever-infected well and the climate and conditions were such, that even the natives of the town fell ill. Many soldiers succumbed and eight out of ten of our guard died. During the intense heat, malaria, typhoid and dysentery attacked the prisoners, so that all, men, women and children, were sick at one time. There were no doctors, no medicines, no proper food, and no treatment of any kind. "I used to make broth for the people, and as I had much practice, I make good broth," said ‘Abdu’l-Bahá laughingly. At this point one of the Persians explained to me that it was on account of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá's wonderful patience, helpfulness, and endurance that he was always called "The Master." One could easily feel his mastership in his complete severance from time and place, and absolute detachment from all that even a Turkish prison could inflict.

In Minneapolis a Jewish Rabbi came to ‘Abdu’l-Bahá with a request that He speak in his synagogue. Part of their conversation reveals the Master’s radiant acquiescence in time of adversity.

‘Abdu’l-Bahá began speaking to him by saying, ‘I have come from your real country Jerusalem. I have passed forty-five years of my life in Palestine; but I was in prison . . . ‘ ‘We are all in prison in this world,’ responded the Rabbi. ‘Yes, I was imprisoned in two prisons.’ The Rabbi commented ‘that one prison was sufficient.’ ‘I was resigned even then, and was in utmost joy and happiness,’ declared ‘Abdu’l-Bahá.

The Master said to Mary Hanford Ford, alluding to the restriction of His and His family’s life in ‘Akka: ‘. . . we are all happy because we have the love of God in our hearts. When the heart is full of the love of God it loses consciousness of the body. Then pain is as pleasure, then darkness is as light! If such a one is shut in a prison there are no walls for him, no solitude, he knows not a prison!’

There was a time when ‘Abdu’l-Bahá was in chains. The jailers were amazed that the Master sang and laughed. He informed them they were doing Him a kindness He had wanted to know the feelings of a man in chains. Now He knew!